The Gist: How Did I Get Here

This week, we’ve been looking back and forward, like a shellshocked Pushmi-pullu. This is the Gist.

There is a moment, late in the evening when the Sun has gone down but the world hasn’t quite gone dark.

The deeds of the day are done, but we don’t yet need to start on the next. That’s the time to take a breath and reflect.

The Jabs keep going into people’s arms, racing the threatened vaccine-busting mutations that need unvaccinated hosts to develop.

Until that programme is over, the primary state responses are set on rails. Of course, as any Irish person can attest, a vehicle running on rails will still frequently arrive late, broken or just vanish entirely.

But we are starting to see a look back beginning- debates about what states did right and what they got wrong. In Ireland, the medical system has recognised a few 2020 errors publicly- primarily the lack of focus on residential care homes as requiring PPE.

It’s pretty generally acknowledged this was the result of institutional short-sightedness on the part of the HSE and its managers. The care homes are mostly private, so the HSE hasn’t had direct management responsibility for them. So, when it hurriedly scooped the pot of PPE for Ireland’s health system, it never saw those those elderly people as being within its direct care. Similarly, rules on private staff working in multiple sites were slow to come and only snapped into focus after the damage was done.

The result was the lead anti-pandemic Irish state healthcare institution was instrumental in exacerbating, not preventing, large numbers of deaths of elderly and otherwise vulnerable people.

Institutional thinking always makes outcomes worse, but in a plague, those costs are not abstract. They are counted in lonely funerals of loved parents and grandparents, attended by families who will always carry the trauma of the nature and mourning of their loved-one’s death.

Still, at least we can say that the Irish institutions made an (acknowledged) error. As Dominic Cummings, the former chief advisor to the UK Prime Minister, testified to a parliamentary committee, death on a vast scale was literally part of the UK’s plan.

Most of the reporting on his evidence focussed on his accounts of spectacular personal dishonesty, stupidity and incompetence by the men elected to lead the UK. (He included himself in that, but, you know, not too much)

Certainly, it’s not ideal to have a PM who was so disruptively incompetent and uninformed that his emergency response committee preferred he write a Wiki-quicky book about Shakespeare for cash instead of attending their meetings.

And maybe that was for the best as having a pandemic meeting chaired by someone who reportedly proposes a policy of “Let the bodies pile high” isn’t necessarily what we might term “best practice”.

On top of that, having a health secretary in a time of pandemic who planners come to realise realise they can’t believe even when he assures them he has not sent infected old people out of hospitals as carriers to their own care homes is a stroke of bad luck.

This is like selling black rats as lovely clean family pets for children during the bubonic plague.

But away from the (completely plausible) tales of personal cupidity and blunders, there were the bones of a deeper bleakness.

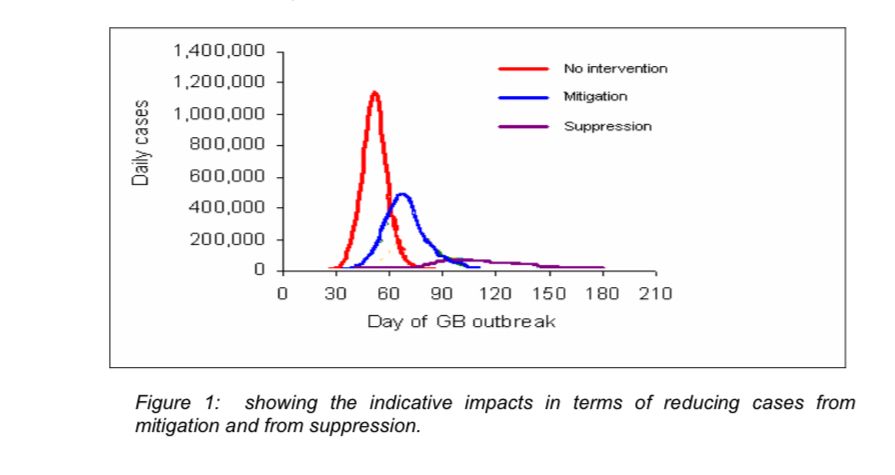

The UK’s 2010/11 national plan for dealing with a pandemic recommended aiming for a level of deaths peaking at around 450,000 a week, with non-pharma steps (social distancing, travel restrictions, advising against mass gatherings and advising hand washing) explicitly rejected on grounds of cost and ‘lack of evidence’.

(See page 54, paragraphs 9.1 and 9.2 of that link if you really want the chills).

The blue line on this chart was the plan, not a warning.

Ireland’s institutional thinking resulted in a fatal blind spot. But the UK’s administrative culture examined the range of options and decided in advance on the mass death of its citizens.

A survey of Irish people released last week reported that only 12% of Irish people would trust the current UK Government. Given what we’ve learned, the only wonder was how high that figure remains.

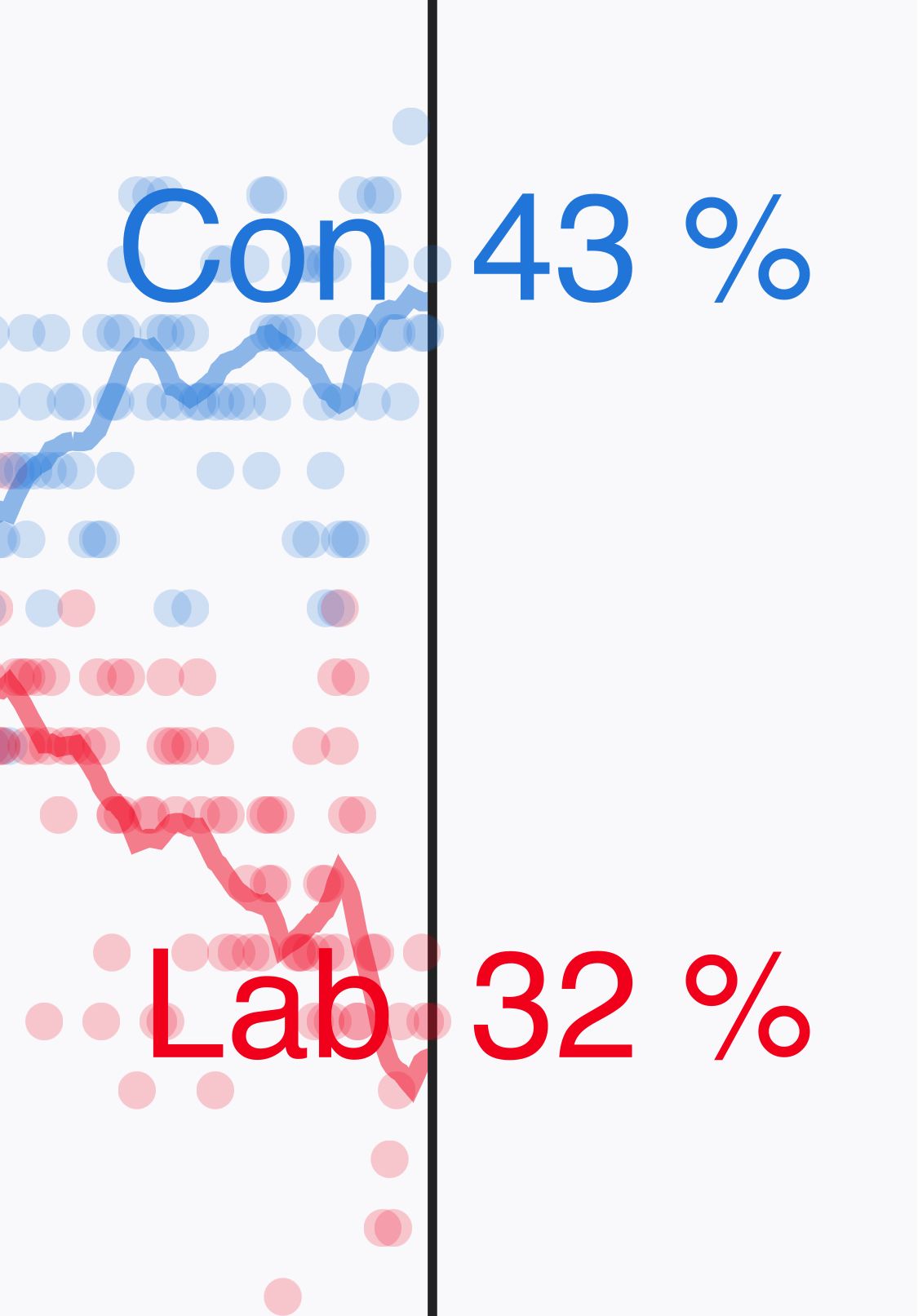

But not as remarkable as the simultaneous news that the Tories had increased their lead over the Labour Party with the UK electorate.

Consider the two trust figures a natural experiment on the effect of two different media ecosystems in covering the same events.

If open Bond-villain style plans to actively choose the killing of hundreds of thousands of people can’t overcome media boosterism and propaganda, the UK may become the first Western locus of a very bleak version of 21st Century politics.