The Gist: AI, a talking dog for the 21st Century.

Séamas O'Reilly on the year's biggest con, AI. This is a Christmas Cracker Gist.

An invited essay by Séamas O'Reilly

Joseph "Yellow Kid" Weil is something of a legend.

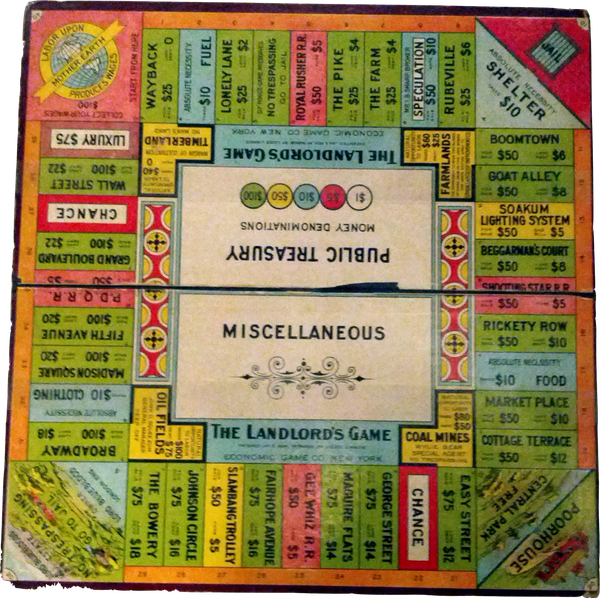

The self-proclaimed “master swindler” was the paragon of the early twentieth century con man. In his time, he posed as the immaculately tailored owner of a talking dog, a medicine show huckster, an oil-field prospector and an infinite number of prestigious businessmen reluctantly cajoled into sharing a surefire stock tip - for a price.

He plied his trade on street corners, boardrooms, race-tracks and betting shops, separating his marks from their money via means so ingenious many of them have lived on a century later. If you’ve seen the ruse which serves as the centre point of 1973 crime caper The Sting, you’ll know one of his greatest hits; the fake bookie’s shop, staffed with dozens of stooges, all working in concert to con one rich mark out of his money. He’s said to have scammed Benito Mussolini out of $2 million and, in 1899, was widely reported to have sold a perfectly unremarkable chicken to an oil baron for the measly price of a thumb sized piece of pure gold. That last wheeze was, in fact, so widely reported that it lives on in the foodstuff which was subsequently named in his honour; the chicken nugget.

In Weil’s marvellous memoir, Con Man, there is scarcely a paragraph that doesn’t induce lip-smacking glee at his audacity, or the bottomless reserve of credulity he encounters from sober, serious people who, surely you think, should know better. His true genius, conveyed in great detail, was in diagnosing the psychology of the mark, which is to say the psychology of the human soul. In the business of offering “something for nothing”, the person you’re conning is almost always your co-conspirator.

"Each of my victims” he writes, “had larceny in his heart.".

I return to Weil’s scams, and his judgments of human nature, often. I see them each time, say, a billionaire runs for the American presidency on a platform of helping the downtrodden by cutting taxes for his wealthy friends, or a cohort of British elites succeed in selling ‘sovereignty and independence’ for the measly price of a place within the world’s largest trading bloc. Increasingly, however, I see it most prominently in the vaunted halls of tech, and nowhere more regularly than in the field of AI.

The Hated Helper

To be clear at the outset, there are obviously elements of AI which show promise. The elimination of many rote and tedious tasks in our daily labours should be greeted as a boon, and AI’s work in highly specialised and technical tasks could prove more exciting still. Early developments in linguistics and pattern recognition already suggest that AI could, and hopefully will, lead to terrific advances in everything from ancient translation to early diagnosis of disease. In such use-cases, however, there is very little guff about this technology’s sentience, nor mention of that dreaded unicorn “artificial general intelligence”. They are simply ingenious and exciting tools which have solid and encouraging applications but do not, crucially, gesture toward an omniscience that does not exist, and which be undesirable if it did.

As an ordinary internet user, I despise almost every in-road into my life that AI has made in the past few years, from incompetent chat services to bafflingly inchoate Google search functions, and the deadening churn of bots on every social media platform left alive. There are dozens of terrible AI versions of my own book being freely sold on Amazon, one of which I even bought in a futile attempt to scry its contents for some form of meaning.

As someone in the creative field, I am sympathetic to the most common critique of AI within that sphere – namely, that its ‘artistic’ output amounts to lazy, error-riddled garbage which is morally and stylistically repulsive, while plagiarising and undercutting actual human artists – but this only nibbles at the edges of how I feel about the topic. Because my main problem with AI is not that that it creates ugly, immoral, boring slop (which it does). Nor even that it disenfranchises artists and impoverishes workers, (though it does that too).

Would Sir care for a Poisoned Baloney Sandwich?

No, my main problem with AI is that its current pitch to the public is suffused with so much unsubstantiated bullshit, that I cannot banish from my thoughts the sight of a well-dressed man peddling a miraculous talking dog.

The claims made by AI evangelists are so broad and plentiful that compiling a pleasingly long paragraph of purported use-cases is as simple as Googling “AI + [noun]”. Having now done just that, I am happy to report that AI will apparently make you rich, find you a date, make you a better lover, a better parent, a better writer, a better worker, a better boss, a better person, a better soldier, will fight all wars, end all wars, hobble terrorists, empower terrorists, make you immortal, end crime, cause crime, solve the housing crisis, revolutionise architecture, cure cancer, and make you a perfect creamy fettuccine with pineapple and cashew sauce.

Some of the above links are more nuanced in their prescriptions, but all advance the same basic claim: AI has world-changing implications for just about every concept or phenomenon you can name, and several you can’t. The problem is, AI is not only unfit to do many of those tasks better (or even more cheaply) than humans, but if it was, in several cases, I’d set fire to every server farm I could find and urge you to do the same.

Let’s take Large Language Models as an example, since they’re the most well-known piece of broadly usable AI tech on the market. Much of their notoriety stems from the fact that its hallucinations are so infamous as to be cliché. We all, I’m sure, have our favourites, like meal planners that recommend putting glue on pizza and eating three rocks a day; mushroom foraging bots which suggest users cook and prepare entirely fatal fungi; or supermarket apps that cheerfully prescribe recipes for “aromatic water” AKA chlorine gas.

It should be observed that such examples are not merely failures because they advocate things that kill their users (although this is not ideal) but because they take the place of existing repositories of information which had little-to-no use case for replacement. In so doing, they’ve also managed to muddy the waters of online information gathering to the point that that even if we scrubbed every trace of those hallucinations from the internet – a likely impossible task - the resulting lack of trust could never quite be purged. Imagine, if you will, the release of a car which was not only dangerous and unusable in and of itself, but which made people think twice before ever entering any car again, by any manufacturer, so long as they lived. How certain were you, five years ago, that an odd ingredient in an online recipe was merely an idiosyncratic choice by a quirky, or incompetent, chef, rather than a fatal addition by a robot? How certain are you now?

Bubble, Bubble, toil and trouble

Some quibble and say that these are just teething problems, the inevitable – even amusing – first steps of a technology finding its feet. But that next step, itself, seems illusory. The scaling of AI to something more workable will require geometrically more investment and computing power than the squillions it has already swallowed up on its path to being the current shit product that nobody trusts. Even enthusiastic reporting on the success of OpenAI, the makers of ChatGPT, can’t avoid mentioning that the company is on track to lose $5 billion this year. Up to now, their financing has been driven by massive cash injections from the same cheery ranks of hedge funds, soft banks, and petrostates which have propped up every loss-making company you can name for the last decade, from Uber to WeWork to FTX.

As recently as July, we saw signs that the market might not be quite as enthusiastic about doing so anymore. It may not be a bubble, but it certainly looks reasonably bubble-shaped, leading tech writer Ed Zitron to convincingly argue we should be referring to the sector as “Subprime AI”. Cory Doctorow goes further in arguing our only task going forward should be working out what kind of bubble it is, the kind that leaves something behind, or the kind that does not.

The cost, both financially and in terms of energy resources, of making good on the promises of Artificial General Intelligence are so vast as to approach Death Star numbers, before we even contend with logistical problems of training AI in the first place. The pool of real-world information on which AI has yet to be trained is not merely dwindling but is, itself, now so polluted by AI-generated content that this task is rendered more difficult still. Chlorine gas air defusers and superglue pizzas are all well and good when they’re merely poisoning amateur cooks, but they have also poisoned the very well from which AI must now train itself, and separating out the hallucinations from real information grows more difficult with every line of robot doggerel these same companies ceaselessly barf into the digital ether.

Automating the Evil Henchman Industry

All of which is to elide the real harms of this technology we currently see in the world around us. In his recent, and spectacular, takedown of current AI orthodoxy, The Phony Comforts Of Useful Idiots, Edward Ongweso Jr lists some harrowing examples, such as the incompetent crime detection software currently putting American criminal justice in the hands of the machine, the discriminatory welfare algorithm which wrongly accused 26,000 Dutch families of fraud, and the ongoing use of AI to enable the ‘mass assassination factory’ of Gaza. In all such cases, AI’s “errors” are both devastating, and hard to even label as errors at all, so much as a bleakly useful abrogation of responsibility for the bad actors intent on protecting the dystopian interests of those in power. It is not the thought of eight fingered portraits or garbled auto-generated novels which prompt me to indulge in cheery reveries of burning server farms to the ground. It is the spectre of yet more dehumanised populations, preyed upon by dehumanised systems of state violence.

I hate AI because it does not work at most of the things its promoters claim it does, and many of the things it does do are explicitly evil. Its missteps not only kill but dissolve the fragile fabric of trust in information we have left. The jargon of AI boosterism, like NFTs and cryptocurrency before them, has seized the imaginations of punters and investors who believe they’re being led to a world of ease and profit that will change the world and make them filthy rich in the process. It’s the last true “something for nothing” we have left, delivered via mechanisms so abstruse to the lay person that its powers can be described with the folkloric hyperbole of a magic chicken.

As a teen, I first encountered Arthur C. Clarke’s famous maxim, “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”, and marvelled at its concision. I was too slow, however, to realise the transitive property hidden within his neat equation: if all technology is just magic we don’t yet understand, then any old bollocks can be marketed as technology, so long as it’s conveyed to us via a mage class of tech wizards with a passion for turtlenecks, eugenics, and the removal of vowels from proper nouns.

It’s a boom time for our new medicine men.

Joseph Weil has nothing on them.