Mothers, Babies, Homes and their Data

The Government rammed through a piece of legislation taking possession of the data collected by the Commission of Inquiry into Mother and Baby homes, planning to seal it for 30 years.

The Minister has made a statement on the Government’s legal position on the application of the GDPR to ... well, to what exactly? Let’s look at it together;

This is the Gist.

My Department has engaged extensively with the Attorney General's office on this issue and the advice we have received, to which the Department is bound, is that the GDPR right of access to personal data set out in Article 15 of the GDPR is expressly prohibited by section 39 of the Commissions of Investigation Act.

Then he explains further;

Section 39 of the Act prohibits that in accordance with Article 23 of the GDPR, which allows for exceptions to the GDPR in a range of circumstances including those relating to the administration of justice. It is on that basis that the Attorney General has advised my Department that the potential solution to the issue of access to information, which a number of Deputies have suggested, is not available.

Really?

Firstly, oh dear.

A national law can’t overrule an EU right, especially not one directly derived from the Charter. It certainly can’t prohibit it.

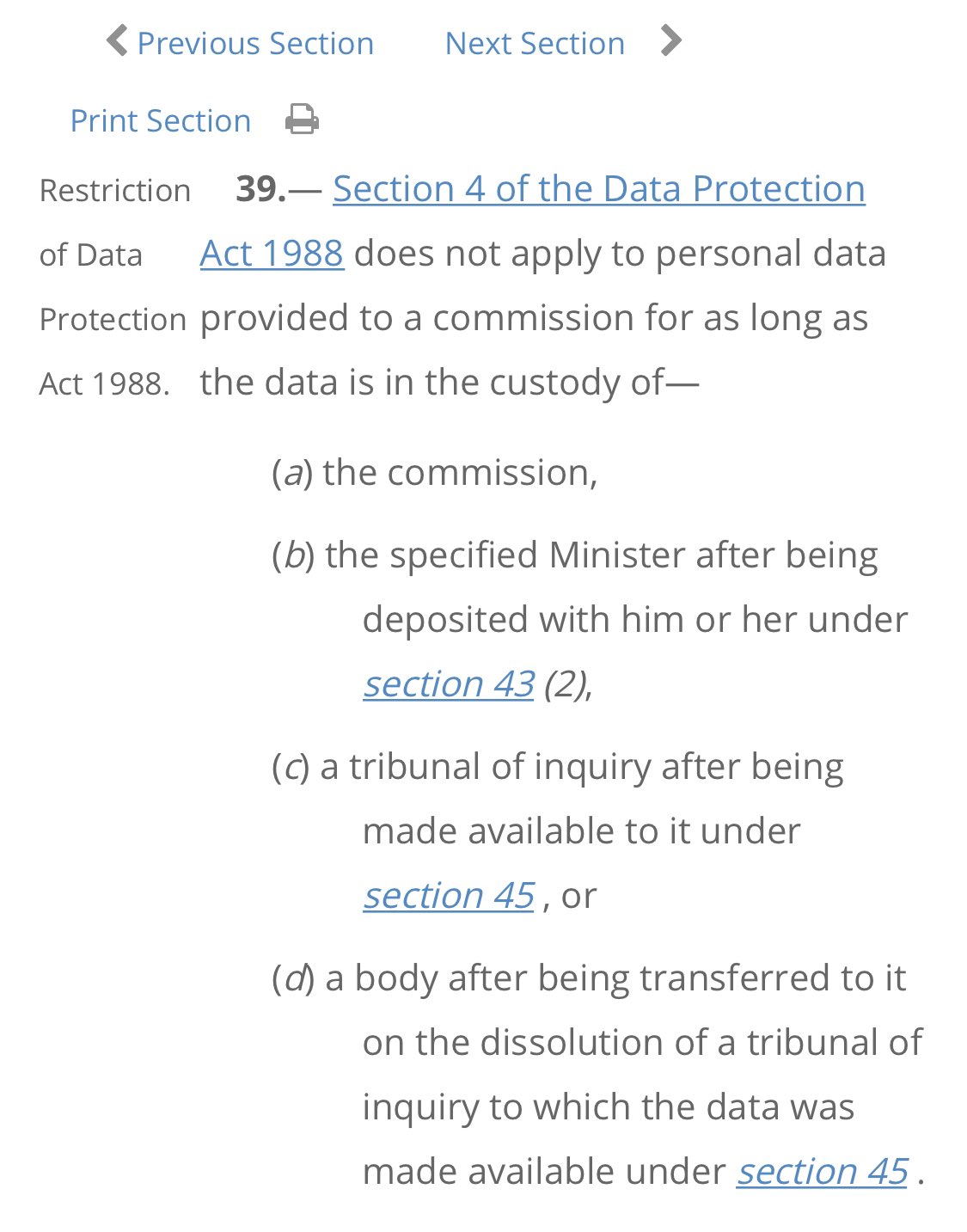

Let’s all go look at Section 39, the impressively muscular piece of the Commissions of Inquiry Act 2004 which the Minister says can prohibit bits of EU law. Let’s have a peep at the words.

It’s not long, don’t worry. It’s quite straightforward.

Now, firstly, as Minister for Justice and The Commissioner of An Garda Síochana v WRC (Case C-378/17) confirms, sometimes there are national laws that just aren’t legal. Laws that conflict with EU law are, strange as it sounds, illegal laws. And the state must just ignore them.

The Court said;

It follows from the principle of primacy of EU law, as interpreted by the Court in the case-law referred to in paragraphs 35 to 38 of the present judgment, that bodies called upon, within the exercise of their respective powers, to apply EU law are obliged to adopt all the measures necessary to ensure that EU law is fully effective, disapplying if need be any national provisions or national case-law that are contrary to EU law. This means that those bodies, in order to ensure that EU law is fully effective, must neither request nor await the prior setting aside of such a provision or such case-law by legislative or other constitutional means.

So Section 39, says the AG, the Minister tells us, exempts the records from Article 15 Data Access Requests. Except, as you can see above, it doesn’t. It doesn’t even mention Article 15 and the GDPR. It couldn’t, because it was passed in 2004 and the GDPR was passed in 2016.

Instead it attempts negation of Section 4 of the Data Protection Act 1988. And that Act isn’t the GDPR. It isn’t even still alive.

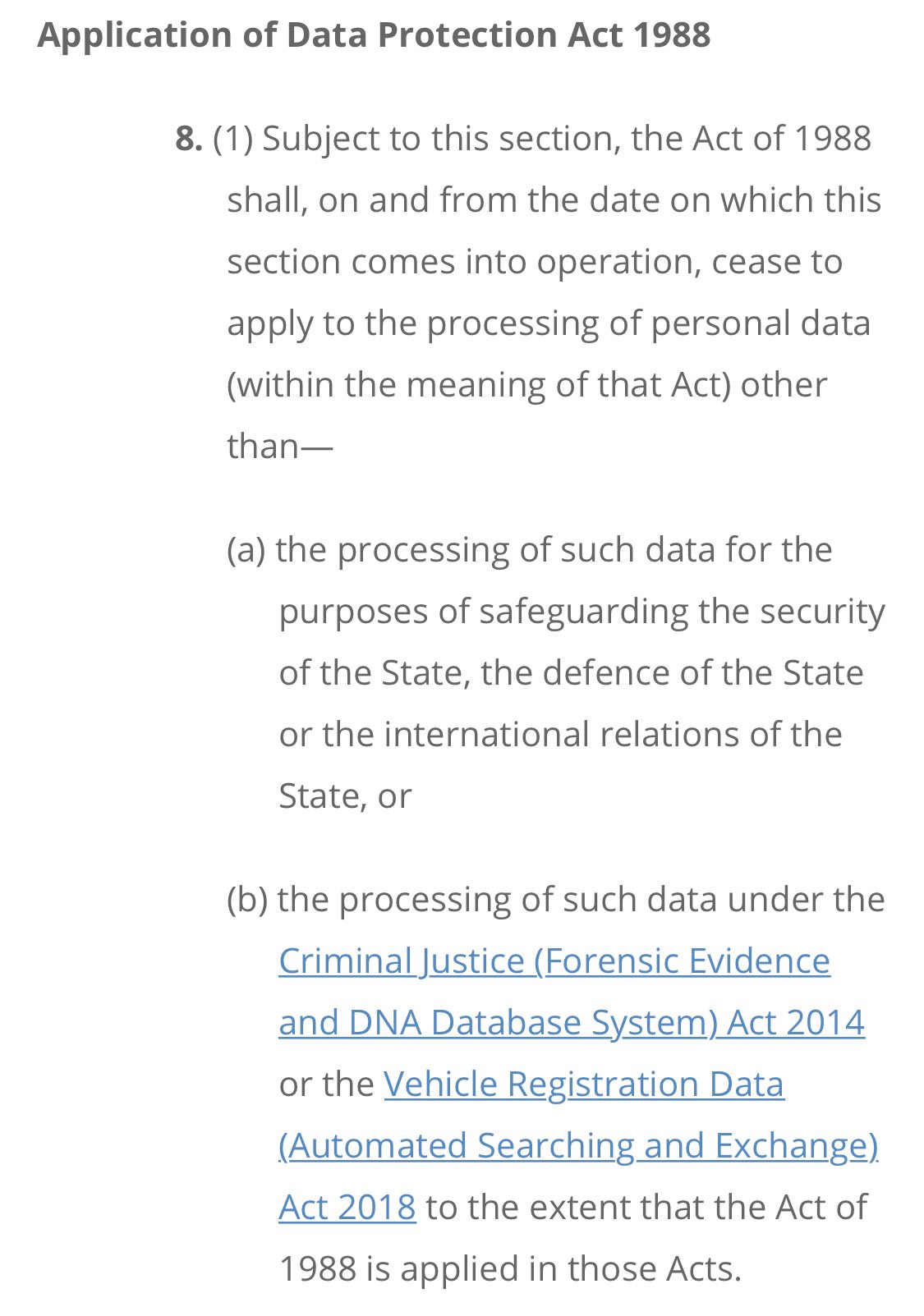

The 2018 Data Protection Act deals with the status of the old 1988 Act which this Section 39 addresses. It was almost all repealed. Two acts were specified as able to rely on it still. Neither was the Commissions of Inquiry Act 2004.

Here, don’t rely on my word for it. Read it yourself;

To recap, the Ministers says the AG told him that a section of a national Act, which refers to a repealed law, prohibits the functioning of an EU Fundamental Right under the Charter. This is deep into what might be termed “novelty”.

But if we’re down in this Governmental rabbit hole we might as well go on and meet the Queen and play the croquet match to the end.

Let’s go check how this time travelling 2004 law can rely on a 2018 Regulation provision to cancel that same EU law. Time to look at Article 23. “Restrictions”

Before we go in, let’s remind ourselves of the Minister’s claimed basis, on which his entire position rests, for asserting Section 39 of the 2004 Commissions of Inquiry Act can oust people’s GDPR data access rights. An exception “relating to the administration of justice.” OK.

But even if Section 39 of the Commissions of Inquiry Act 2004 was relying on an exemption that was actually one of the existing grounds for restricting GDPR rights, It still wouldn’t make it legal. You see, Article 23 has a second section, setting out requirements for national restriction laws. No requirements, then the law (and its restriction of rights) is invalid.

23.2 In particular, any legislative measure referred to in paragraph 1 shall contain specific provisions at least, where relevant, as to:

(a) the purposes of the processing or categories of processing;

(b) the categories of personal data;

(c) the scope of the restrictions introduced;

(d) the safeguards to prevent abuse or unlawful access or transfer;

(e) the specification of the controller or categories of controllers;

(f) the storage periods and the applicable safeguards taking into account the nature, scope and purposes of the processing or categories of processing;

(g) the risks to the rights and freedoms of data subjects; and

(h) the right of data subjects to be informed about the restriction, unless that may be prejudicial to the purpose of the restriction.

And Section 39... ain’t it.

To recap: The Minister described advice given by an unspecified AG on an unknown year (which may or may not be from before the coming into force of the GDPR) which said that an Irish law can prohibit an EU right, despite it limiting a different repealed law, based on a non existent restriction clause, which would anyway require a series of protections which it doesn’t have to be valid.