The Gist: A safe pair of hands

The counts continue, but the dust is settling over some surprising results. This is the Gist.

Every election is an adventure and every count a revelation. Nobody knows what's going to happen when people are presented with two foot of ballot paper and a series of unflattering portraits of both the candidates and, by extension, their own neighborhood. Anyone who tells you they do know what will happen in advance is either selling you their polling services or will also claim to be getting messages from beyond the veil as to where your late Great Aunt Mabel hid the family silver.

We've had a superabundence of narratives generated since the boxes of both the Local Authority and European Parliament elections were opened. Meaning has been imposed and superimposed, to the extent that it can be a bit hard to see what actually happened behind all the stories already building up around the events.

Let's run through the library of Just So tales, and see what we might make of them if we, too, peep behind the veil.

Sinn Féin Flop

This is the main story coming out of the election. But Sinn Féin actually increased their number of seats held, compared the last election in 2019. In 2019, Sinn Féin won 81 seats out of 9.5% of the first preference votes. This time they got 11.8% of the first preference vote and won 102 seats.

The problem for the party is that 2019 was widely seen as a disaster of a result for them. They weren't even thinking of that being the bar to get over this time. The party has been floating in the 20s in polls for years, sometimes bumping up into the 30s in terms of party support. Everyone agreed they left seats on the table at the last general election because they didn't run enough candidates. This time, determined not to repeat the mistake, Sinn Féin ran more candidates. More than they could ever get elected. A lot more. Not since the heyday of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics has one party put so many candidates up in one election.

This is an excellent way to split your vote, missing out on seats that might have been won, if you just don't have the first preference juice to start with. And, on 11.8%, this was a shrivelled, dry and juiceless election for Sinn Féin.

We'll look at why in a minute.

Fianna Gael: one party, two heads

We've grown used to the idea of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael working together in government. Whether in formal coalition or with a confidence and supply agreement, the two parties have been shoring each other up since 2016. Over that time, the voters for each of the parties seem to have become happy with this arrangement. In this election, transfers between the old enemies flowed as though they were, in fact, the same party.

In 2019 the parties got

| Party | Seats | FPv% |

|---|---|---|

| Fianna Fáil | 279 | 26.92 |

| Fine Gael | 255 | 25.26 |

This year they got

| Party | Seats | FPv% |

|---|---|---|

| Fianna Fáil | 246 | 22.95 |

| Fine Gael | 245 | 22.99 |

Stripped of expectations from the polls, this looks more like gentle and managed decline than a barnstorming result.

“Nazis! I hate Nazis!”

The press worked themselves into an unseemly lather in the weeks leading up to the election about the novel prospect of Ireland electing a banc of far-right candidates on an explicitly anti-immigrant platform.

Some of the political parties panicked at this prospect and were at pains to signal to voters that they, too, could be relied upon to be racist and callous also. Sinn Féin, in particular, seeing their poll numbers sagging, responded by sweatily reacting to the volume of online mouth-breathers as though they indicated a nascent mass movement.

In reality, the assembled ranks of Twitter’s Musk-scented sock puppets struggled to elect a bare handful of local councillors. Each one a shame to their electorates, of course, but nothing close to any kind of political force.

STV, The Joy Division

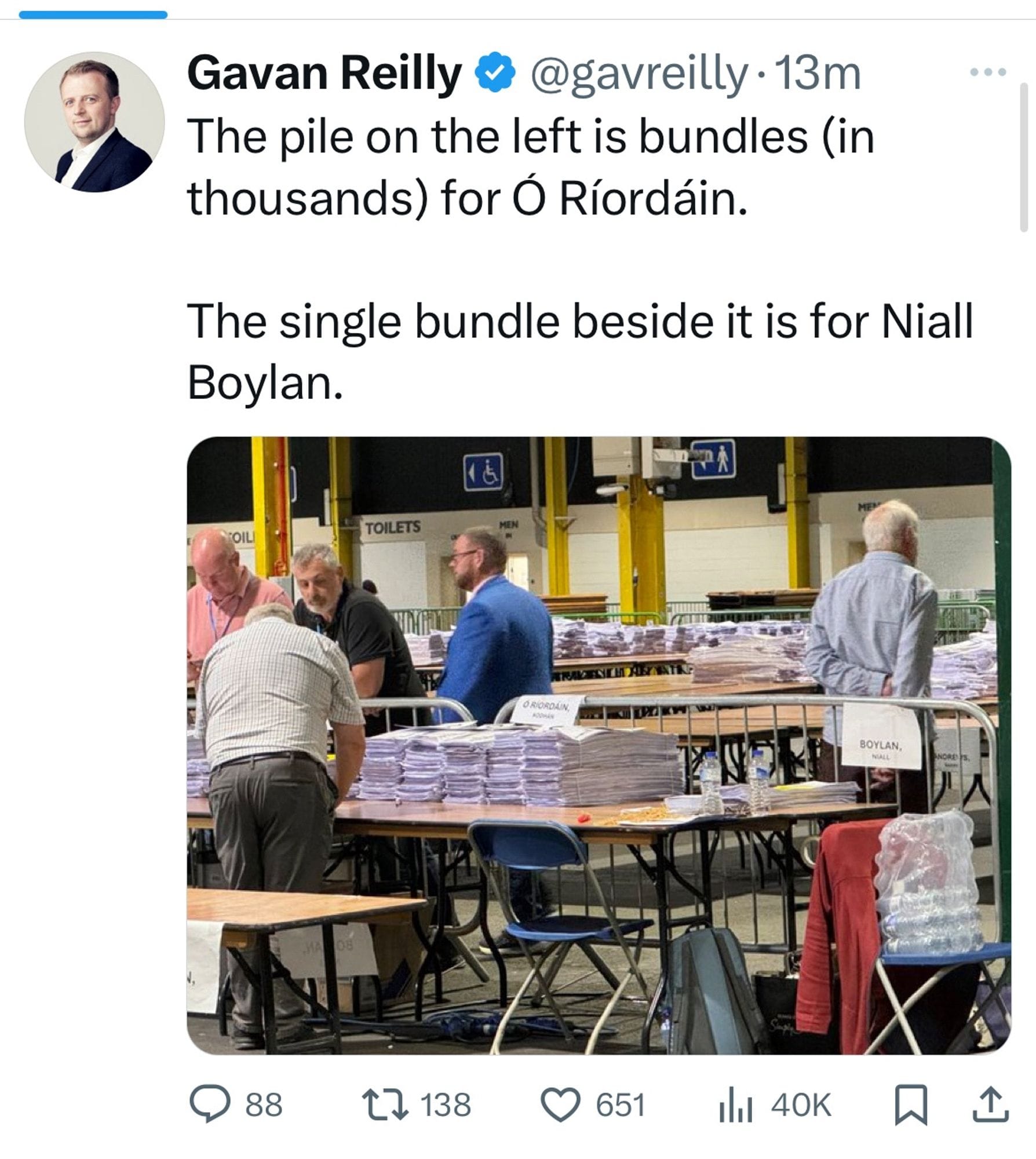

Perhaps one of the sweetest moments of democratic Karma was when Dublin Euro candidate Niall Boylan- who spent many of the empty years of his life griping about people who cycle bikes- found his political career was ended before it started by transfers from Green party voters pushing his Labour Party rival ahead of him into the last seat.

What have we learned?

The essence of a Just So story is that it works backwards from what can be seen (elephants have long trunks, Fine Gael only lost 10 seats) and creates some tall tale to explain it (A crocodile stretched it out and Simon Harris’ personal charisma has thrilled the public).

And, like a Just So story, a political narrative’s main purpose is not to be true but to be a tale to amuse and amaze.

But, as should be clear to all readers by now, the Gist is staunchly indifferent to amusement. So here is a plain, rather dull, account of these election results;

The people who turned out to vote took the threat of the radical right seriously, and decided to plump for candidates who seemed like a safe pair of hands.

Sinn Féin’s massive slate of candidates meant a massive slate of unknowns being presented to the electorate. The talent bench for any political party always has a maximum depth. After that, you risk voters meeting your C or D candidate as the party’s representative. If, like me, you are told on your doorstep that the Plan is to vastly increase services delivered by the local authority while also abolishing the tax that funds 35% of the current services most people will spot a lack of seriousness.

Similarly, any party willing to pivot so easily to dog whistles on immigration is a party whose claim to champion the left-wing will be looked at askance.

In the end, it may be more basic than even that. Over the last five years the tide came in for Sinn Féin and then it went out again, and they never got the good of it. The next election may see more of the same as we got here, or it may see some other party catch the wave. But I can’t see the moon pulling the votes in SF’s favour again this year.

Parties can make good and bad decisions about what to do, and those decisions matter. But, despite the efforts of the latter-day Kiplings whose jobs rely on explaining how one thing led to another, sometimes all they can do is hope.

Which, as a voter, is all you can ask of an election.